Isaiah 40:1-11; Psalm 85:1-2, 8-11; 2 Peter 3:8-15a; Mark 1:1-8

What are we to make of the ancient poetry of hope-for-a-final-age that marks this season. We

are familiar with scenes of violence from all over the world, both large-scale and small.

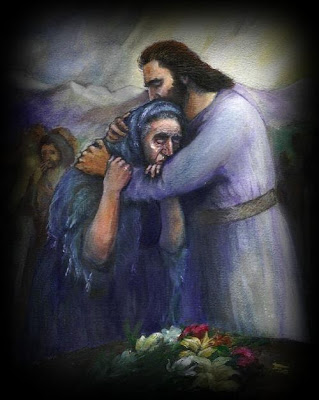

Nevertheless, the Church proclaims scriptures which announce valleys being filled in,

mountains being brought low, and the Lord God feeding his flock and carrying them like lambs

in his bosom. The readings are undoubtedly visions of peace. Without a people who share this

vision, are convinced by it, long for it, the tide of violence can only rise and humanity be even

further engulfed.

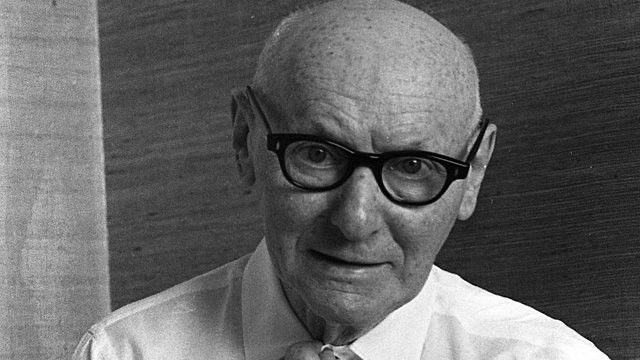

Another great Jewish storyteller, Isaac Bashevis Singer (1903-1991) won the Nobel Prize in

Literature in 1978. During his acceptance speech in Stockholm he made the case for the

storyteller, the poet. Such are Isaiah, the author of 2 Peter, and Mark. Singer said:

In the history of old Jewish literature there was never any basic difference between the

poet and the prophet. Our ancient poetry often became law and a way of life…. While

the poet entertains he continues to search for eternal truths, for the essence of being.

In his own fashion he tries to solve the riddle of time and change, to find an answer to

suffering, to reveal love in the very abyss of cruelty and injustice.

Was the nameless poet we call the Second Isaiah – the one whose work of genius begins at

chapter 40 with the first reading – trying to entertain? Was the author of Mark’s gospel? You

can be sure both were. The moralist, the doctrinaire preacher of an ideal merely tries to

improve the occasion. The artist, however serious of purpose, know that unless she gives

pleasure there is not art.

The storyteller [said Singer] ….must be an entertainer of the spirit in the full sense of the

word….There is no paradise for bored readers and no excuse for tedious literature that

does not intrigue the reader, uplift the reader, give him the joy and the escape that true

art always grants.

When the Polish-born Singer spoke of the Yiddish language, his lifetime vehicle of expression,

he praised it for its power to convey “pious joy, lust for life…patience and deep appreciation of

human individuality…[and] longing for the Messiah.” Those poor ghetto Jews, like the New

Testament writer and the prophets before them, knew that “there must be a way for a man to

attain all possible pleasures, all the powers and knowledge that nature can grant him, and still

serve God.” We Christians, like our comrades in hope and longing – the Jews – call that dream

of total fulfilment “the days of the Messiah.” We keep hoping even though Jesus has come,

because we have not admitted him fully. We are in the painful condition of knowing the

difference between what could be, in him, and is.

Isaac Singer said that as a child he heard from his older brother all the arguments that

rationalists brought out against religion. The writer of 2 Peter was besieged by them. “The Lord

does not delay in keeping his promise,” he answered, “though some consider it delay. [There

are somewho mock and sneer who will ask]: ‘Where is that promised coming of his? Our

ancestors have been laid to their rest, but everything stays just as it was when the world was

created’” (v. 4). The sacred author says that God delays because he wants to show generous

patience. “He wants none to perish but all to come to repentance” (v.9).

Singer praised the Yiddish mentality, which he said was not haughty.

It does not take victory for granted. It does not demand and command but it muddles

through, sneaks by, smuggles itself amidst the powers of destruction, knowing

somewhere that God’s plan for Creation is still at the very beginning.

We must not forget that Singer was one of Jesus’ people and of which he speaks. Unknowingly,

he describes the poetry of the Advent liturgy. It is not a poetry of triumph but of hope. We live

in a world that is literally one of desolation. Peoples are committed to the destruction of other

peoples. Billionaires become ever richer while heads of families despair of supporting their

families. Resort hotels prosper while populations I the vicinity scavenge for garbage by night.

The gap of income, wealth, and power grows in the world, much of it in favour of countries that

have been wont to call themselves “Christian.”

The Advent spirit is, indeed, the Yiddish spirit, the Jewish spirit. It is not proud. It hopes where

there is no human ground for hope. It asks for God to come and vindicate his own – through

Jesus – “the son of a people who [have] received the worst blows that human madness can

inflict” [Singer]. It waits on a God who speaks in deeds not in words, and whose vocabulary is

the cosmos.

Kevin+

Recent Comments